The frightening future – no jobs for humans. Or not?

When I was President of the Globe and Mail, I had the chance to ask the venerated Barbara Frum, “What makes a good story”. She thought for minute and said, “One that tells people something they don't know about something that is important to them”. In Ireland, where I grew up, they say, “don't let the facts spoil a good story”.

When we read every day those terrifying forecasts that computers will take over our jobs, will rule the world and maybe decide that the best way to deal with global warming is to eliminate humans, it is worth bearing both of the above quotes in mind.

Yes, we need to deal with what is happening but we shouldn’t rely totally on what seem to be facts because there are two giveaways that say that they might not be too accurate. First, the forecasts of the number of jobs that will disappear is between 20-60% – they can’t all be right. Second, in many of these research studies, the jobs that will be least affected often turn out to be researchers. Makes you wonder.

So what is the answer? Definitively – many jobs will disappear, many will change, new ones will appear – but no one has the slightest idea how many, when or how.

Take a simple example. Today, a multitude of people are employed making, moving, marketing and merchandising the thousands of brands of deodorants, hair conditioners, shaving cream and detergents we use today. One hundred years ago, we used homemade lye soap. Would anyone have been able to come close to estimating the impact of changes in technology in this industry?

Inevitably what automation does is cut the cost of making anything. This reduces prices, which in turn, through the magic of economic theory and elasticity curves, increases volumes. And so employment goes up. Sometimes it is directly tending to the machines, in other cases, in related creative task that have not been automated.

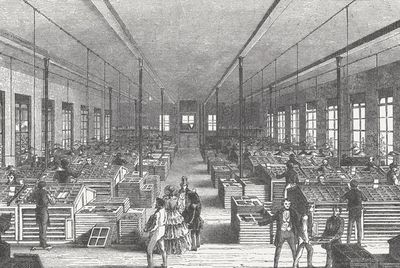

Take weaving: the poster child for the Industrial Revolution. James Bessen, an economist at the Boston University School of Law, found that during the 19th century “the amount of coarse cloth a single weaver could produce in an hour increased by a factor of 50, and the amount of labour required per yard of cloth fell by 98%”. In 1900, there were four times as many employed in the weaving trade as there were before automation was introduced

There is a more recent example which I’m closely familiar with. Typesetting related jobs fell by 100,000 during the 1980s, as hot lead type in the printing industry was replaced by computerizes composing systems. However since then, 600,000 digital designer jobs have been created. The new jobs more than replacing the old ones.

Everywhere we look we see the same trend. In the 1800s 50 - 70% of the working population in what are now industrial societies were farmers. Today it’s around 1.5%. ATMs replace tellers in banks. Costs fall, it becomes economical to open more (smaller) local branches.

So what jobs do people have today that (largely) didn’t exist say 100 years ago? Take financial services, tourism, TV and movies, making computers and cell phones – and the software and apps to make them run.

Totally unpredictable.

The key point about automation and the broader concept of an intelligence revolution based on powerful computers, networks and robotics is that it will change the way we work today and offer better outcomes in lower costs, higher quality and improved productivity. But more importantly, it will fragment many industries and that will threaten the slow moving but offer huge new opportunities to the fleet of foot.

The key message?

Make sure you closely watch how technology is changing. Be very clear about the business you are in. Regularly update your competitive plans – and remember that neither Uber nor Airbnb came from within the taxi or hotel industry.

Where is your next competitor coming from?